We’d like to introduce to you an underused form of publication: the bookling.

At Guillemot Press we’ve often been presented with manuscripts that are a bit cramped - 12 or 16 pages of poems squashed together - and we just want to give them a little room. We loosen the belt, maybe undo a button, let the poems breathe, and before we know it we’ve got a little book extending to 50 or 60 pages. It’s not really a collection, but it’s not a pamphlet anymore either.

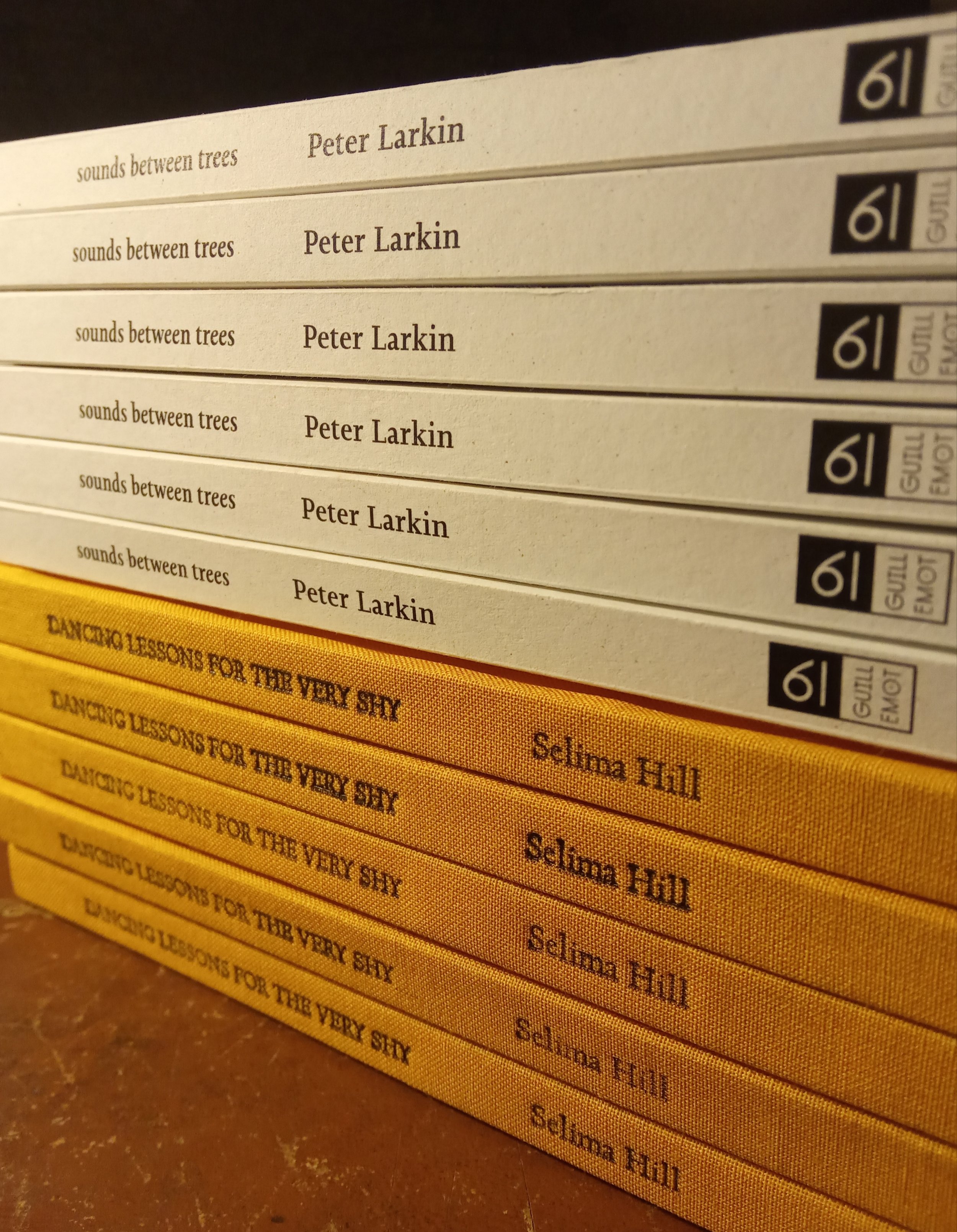

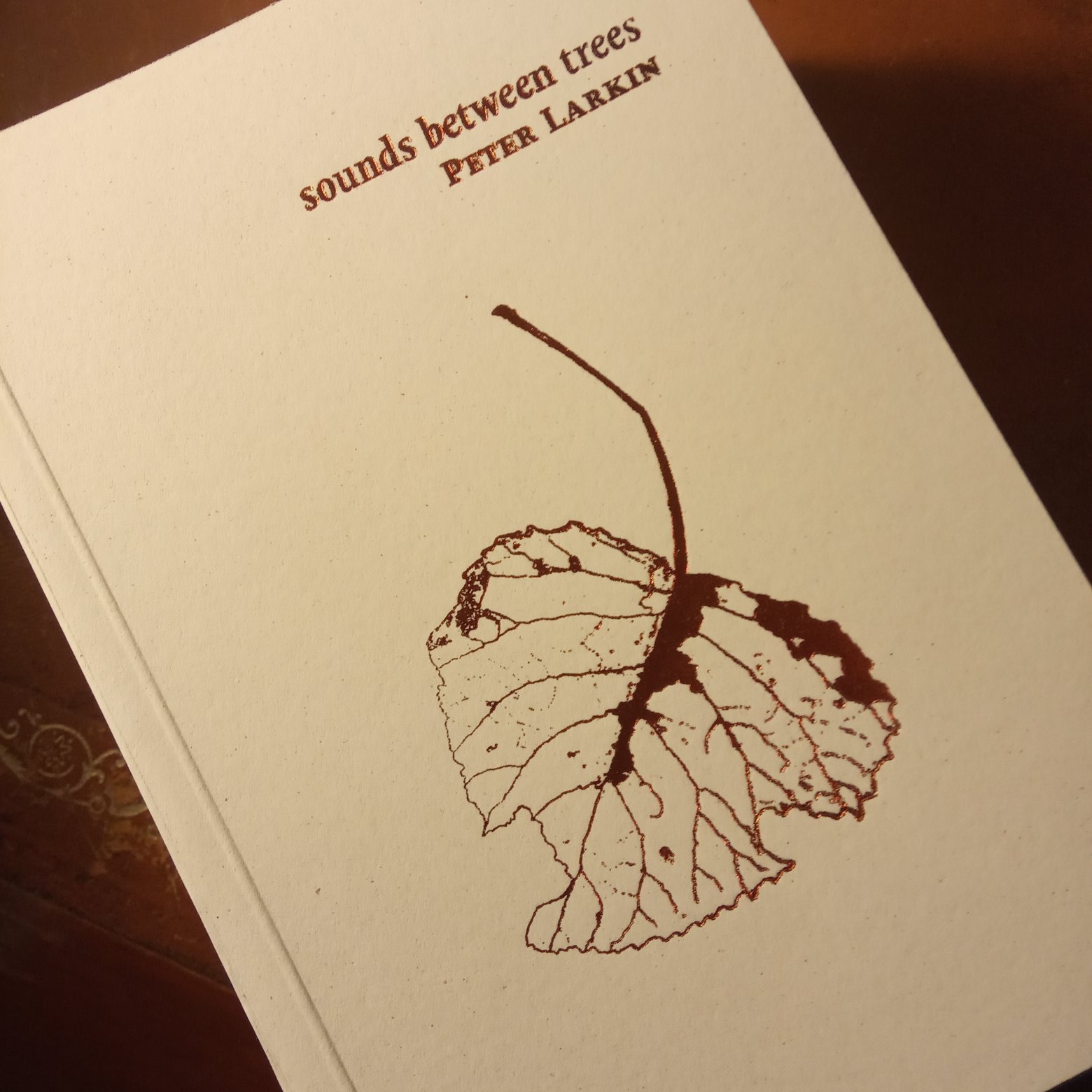

I’m thinking of titles like Peter Larkin’s Sounds Between Trees and Selima Hill’s Dancing Lessons for the Very Shy. Similarly, we sometimes make a little hardcover, as we did for John F Deane’s Voix Celeste and Rosmarie Waldrop’s White is a Color. Both historic and contemporary definitions of the pamphlet tend to exclude these methods of presenting the text. For example, poetry prizes give hard definitions of what a pamphlet or collection can and can’t be. This is where the bookling comes in.

The bookling has been around since at least the 1700s but unlike its cousins the pamphlet and the book, the bookling has not spent much time in the limelight. The pamphlet was the single quire (which could be any length, as long as it was just folded) and the book was made from sewn and bound sections. The bookling, on the other hand, is defined only by diminutiveness. That could be diminutiveness of either extent or page size and it does not come with any expectations of format or finish. I can section sew it, case bind it, illustrate it - I can make a bookling as brilliant and beautiful as I like.

Booklings can be as wild and unruly as they like (and as the pamphlet was in its early life). They are short texts that have dressed to please themselves. There’s a good deal of fun to be had with the bookling, I feel.

Luke Thompson, co-editor