i. Chalk ghosts

THE SLEEPING PLACE project began with my discovery that my family home – the house where I spent my childhood - was not only built on chalk foundations but over the top of what had been a Saxon burial ground. Although initial excavations suggested the location of this cemetery was on the top of a chalk ridge just above my family house, subsequent discoveries found bones and grave sites extending down the hillside and beneath our garden. This haunting discovery was the starting point of THE SLEEPING PLACE.

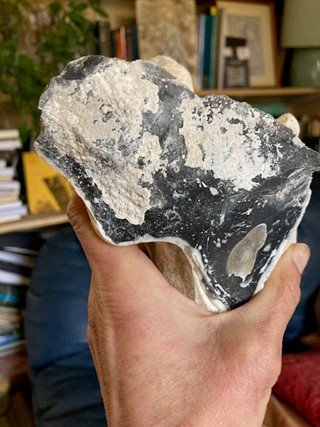

Chalk flint picked up from site of Saxon burial ground, 2023.

The great piles of chalk, excavated to make room for house foundations, and with which my parents later did battle to make their hillside rockery, were knobbly and socketed and vertebrae-like. My imagination was haunted by their memory. We played with these chalk flints as children, piling them up into unstable camp walls, hurling them as missiles, and cradling their cold protuberances like misshapen dolls. But did they include actual bones?

The chalk ridge, on which the Saxon burial ground was situated, forms part of a chalk spine which runs from Guildford towards Farnham and is known as The Hog’s Back. All along this ridge, there are heaps of chalk flints chucked in the corners of fields by exasperated farmers or used to line driveways of newly built houses. Who knows what else came up with the chalk, what skeletons? As I started to explore how I might stage some of this excavation in writing, these bumpy pieces of chalk kept intruding and reminding me of their materiality.

And there were other ghosts. Not only was I haunted by the thought of these unquiet foundations beneath my old home but also by those other skeletons, also white but far more dangerous: the racist myths of a white ‘Anglo’-Saxon past also buried here in the south-east of England.

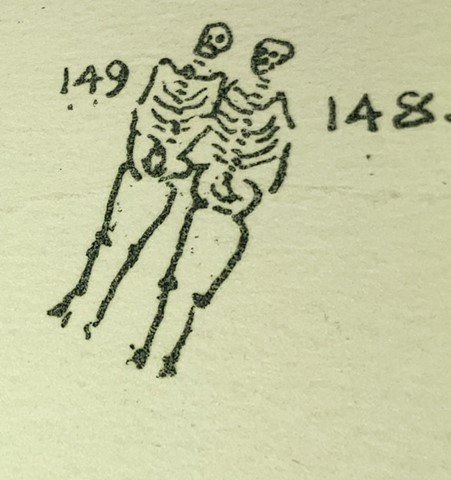

Sketch made in early stages of THE SLEEPING PLACE project.

ii. ‘Three extra heads’: ethical considerations of working with human remains

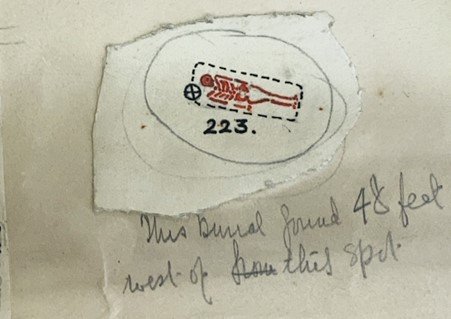

Detail from archive photograph, Saxon burial site. (All such images used here are tinted blue and include a votive chalk piece, added to mark my recognition that these are human remains).

How much time has to pass before human remains become simply museum exhibits? Why should it make any difference whether it is hundred or a thousand years? Why do we regard the bodies buried beneath the marble tombstones of a Victorian cemetery as different from the bones dug up and exposed by archaeological excavations? This is one of the questions that emerged through THE SLEEPING PLACE's explorations, and it led to my use of some personal poetic rituals alongside other more procedural and linguistic approaches used in the composition of this piece. One immediate decision I made when confronting these questions was not to use the archival images of human remains without altering them in some way, as an acknowledgement of the ethical issues around my usage. I have ‘treated’ all these archival images as a gesture, tinting them blue in response to what I find to be their affect and obscuring them with the addition of a piece of chalk used as a votive object.

Almost as I discovered the existence of a Saxon burial ground, England went into its second national COVID 'lockdown', and so I was not able to visit the local museum for many months. However, I was able to access online reports published by the Surrey Archaeological Society. I discovered the earliest part of the burial ground dates back to the sixth century, but the site was in use for burials for the next five centuries. Pagan burials mix with Christian graves, alongside burials of peoples from a variety of tribes. Many of the graves were 'shared', containing the remains of several different skeletons or parts mixed together, suggesting it may have been, for a time, an execution place or the site of a massacre. Alternatively, bones may have been ritually mixed together to make one ancestral body.

My interest was captured by the complexity and multi-layered nature of this site and the way it so dramatically contradicts a nationalist myth of a ‘pure’ and indeed, ‘white’ Anglo-Saxon originary. I knew that I wanted to write about this but how? It was to be a formative conversation with artist-archaeologist Rose Ferraby and my engagement with online extracts from the archival archaeological site maps of the 1920s excavations that opened a way forward.

iii. Poetry as archaeology and the poetics of archaeology

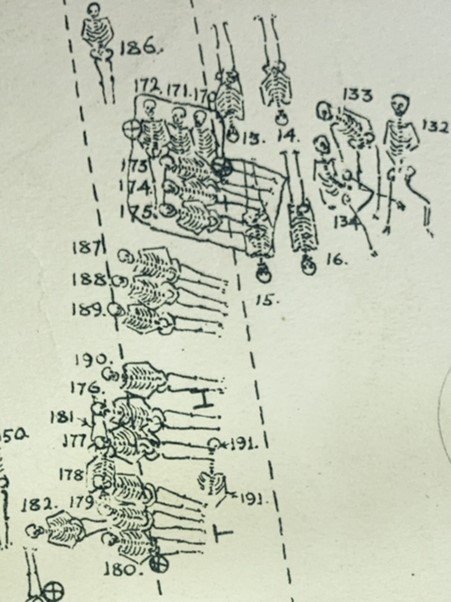

Detail from site plan of Saxon burial ground made by AWG Lowther in the 1920s (this and all images in this essay reproduced courtesy of Surrey Archaeological Society)

Inspired by the multi-layered complexity of this Saxon burial site, I decided to engage specifically with its archaeology. The archaeological records of the 1920s excavations of this site are held in my local museum archive. The main site plan was made by archaeologist A W G Lowther. He led the dig in its final stage, but his plan incorporates the notes and plans made by an earlier team, using a numbering system based on the order in which burials were excavated. The site plan is crowded with layers of finds and multiple burials, a teeming mass of layered information which demonstrates the choices and decisions made by different archaeologists and the way the understanding of the site and its burials kept shifting and changing. Perhaps inadvertently, Lowther's map provides a diagrammatic representation of this site as a one in a state of flux and constant revision.

One of the aims of my project was to deconstruct any essentialist notion of this burial ground as a ‘heritage site’ or as linked with a nationalist myth of a supposed ‘Anglo’-Saxon ‘Englishness’. The provisionality and revisions of this archaeological record struck me as a useful template for an alternative construction of this place as a dynamic series of changing networks and relationships. Conversations with artist/archaeologist Rose Ferraby were formative in how I shaped the poetics for this project and led to the brilliant artwork Rose has produced (thanks to the support of Guillemot Press) as an intrinsic part of the project. Also formative was the book Theatre/Archaeology by Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks (Routledge, 2001). Pearson and Shanks' concept of a ‘post-processual’ archaeology suggests that the task for archaeologists is to forge assemblages which, if they are to be authentic and meaningful, must be volatile: ‘the emergence of new meanings depends on the perception of instability, of retaining energies of interruption and disruption’. This was the start of what became the poetry of THE SLEEPING PLACE. Archaeological excavations of this burial ground are staged as provisional assemblages of language and visual collage out of whose unstable layers, insistent patterning and 'misplaced' anachronisms the reader is invited to re-assemble the past.

The processes of chance and choice, which play an important role in our constructions of history, were brought into my staging of these assemblages by my use of a specific textual constraint based on Lowther’s site plan. I describe this constraint in the Timeline at the end of THE SLEEPING PLACE:

Archaeological site plan made by AWG Lowther in the late 1920s.

March 2021: I decide to use Lowther's site plan not just as a template for my text, but also as its skeleton. The plan shows 223 burials and so I create 223 pieces of text out of an imagined engagement with the material circumstances of the site. Each piece of my text includes a deictic, those parts of speech which establish the spatial and temporal co-ordinates of a piece of writing, but at this stage in my composition they are detached from any presiding subject. They are simply loose fragments of text whose role in place-making or poem-making is not yet determined. Tokens of orientation, they wait for sentences in which to embed themselves as milestones and signposts. Or gravestones.

Late March 2021. I am inspired by the graphic quality of Lowther's plan to read it as though it were a page of text. I read it left to right and top to bottom, turning its burial numbers into a code or pattern by which to combine my text pieces into a whole. I arrange my text fragments into an order suggested by this code. As I do so, words attach to each number, randomly pooling around roots and squares. As the text comes into curious being, its deictics form new syntactic relationships, staging their temporal and spatial coordinates within the poem's newly formed sentences. These coordinates seem both random and plausible.’

This approach to textual construction thus involved me in deconstructing certain aspects of conventional grammar, in particular, deixis. I was inspired by Gertrude Stein’s innovative approach to grammar and her experimentation with the hybrid grammar conventions available within the prose poetry form, which combines or layers the traditions of prose and poetry. By excavating and reconstructing some of these prose and poetic ‘grammars’, THE SLEEPING PLACE begins to play with a kind of linguistic archaeology.

But my work on this project also raises bigger questions about the role of art and poetry in relation to archaeology and formulations of 'the past', and the importance of including a variety of different kinds of response - statistical, performative, scientific, affective, aesthetic etc - within the overall archaeological record. I hope that as part of the publication of THE SLEEPING PLACE there will be the opportunity for further conversation about archaeology, poetry, cultural enclosure and the work of decolonisation.

iv. Satirising ‘Anglo-Saxon attitudes’: Lewis Carroll, white rabbits and decolonisation

Visiting the 'Lewis Carroll' grave, white rabbits in the background.

It might seem strange to make a connection between Victorian mathematician and nonsense writer Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) and my project to engage with the decolonisation of a 'heritage site'. The drivers for my project to stage textually the archaeological excavations of a Saxon burial ground were manifold, but one of them was the compulsion to interrogate the discovery that buried in the back garden of my family home in Surrey were, quite literally, the bones of a violent, nationalist myth of a 'white' and ‘Anglo’-Saxon past.

The hillside on which my family home is situated is not only the site of a Saxon burial ground, it is also the location of a Victorian cemetery, a minor tourist site due to its fame as the site of Lewis Carroll's grave. This grave is the destination for many literary pilgrims and is always decorated with tokens and tributes, including a multiplying number of white rabbits.

Like many graves in this old churchyard, the Carroll grave is now tilted down the steep chalk hill. As the Saxon burial ground spread from the summit of the hill right down to (and possibly beneath) the nineteenth century cemetery, it seemed to my haunted imagination that Saxon skeletons and Victorian bones might be rolling together down the hill, white rabbits and all.

Page pulled from my sketchbook.

Although Dodgson spent his working life in Oxford, he spent vacations in Guildford where he owned the house in which his sisters lived. He wrote Through the Looking Glass in Guildford, and in 1898, he died and was buried there. This played into my project in a number of ways: 'whiteness' is made visible and deconstructed variously in THE SLEEPING PLACE not least through the shrine of plastic white rabbits accumulating on the Carroll grave. Dodgson's phrase 'Anglo-Saxon attitudes' (Through the Looking Glass, 1872) is collaged into my own text. Dodgson was ambivalent about the British colonial expansion lauded by many of his contemporaries and indeed, there are some, not entirely implausible, readings of Alice in Wonderland as an anti-colonialist satire! He coined the phrase 'Anglo-Saxon attitudes' apparently to mock an early drawing style, but the satirical potential of the phrase has been spotted, taken up and exploited, including by novelist Angus Wilson and as the title of a recent conference examining English cultural self-images. But most important for my project is Dodgson's interest in language practices and systems, their role in meaning-making and thus in nonsense-making. I approached the writing of this project with a model of practice indebted partly to Gertrude Stein. Stein is of course a later and very different writer to Dodgson, and yet they share areas of linguistic interest. Stein's experimental writing was often read by her critics as the very 'nonsense' embraced by Dodgson. And that crooked headstone of Dodgson/Carroll's grave, baffling to a sense of the upright, tilts its uncomfortable shadow across the pages of my project.

v. On doodles, art and the ineffable

THE SLEEPING PLACE by Susie Campbell/Rose Ferraby, Guillemot Press, 2023.

Because I had worked previously with Guillemot Press and artist/archaeologist Rose Ferraby, I was able to draw on my knowledge of what they could bring to the realisation of this project if I were fortunate enough to be published by them again. And I built this into my vision of THE SLEEPING PLACE, dreaming of a book as multi-layered as the archaeological excavations it depicts. In the hope that Guillemot and Rose would come on board, I imagined a book whose design and visual artwork would work in an assemblage with the text itself. I am so excited that this imaginary book is now a real book to share with a wider audience.

Detail from Rose Ferraby's artwork (inside THE SLEEPING PLACE).

Early in my discovery that an ancient Saxon burial ground had been excavated beneath the site of my family home, I had the first conversation in what would become a series of formative chats with Rose about art and archeology. We talked about the importance of broadening the archaeological record to include a range of responses to the material traces of the past. These responses might include visual art or a range of other art forms. Poetry of course is one of these forms. I am fascinated by the poetry of archaeology. There is much important work currently being done, including volumes of poetry (Vestiges and Peat) curated by poet archaeologist Melanie Giles with artwork by Rose. Other important books engaging with poetry, archaeology and the landscape are currently being published by Corbel Stone Press, Longbarrow Press and recently, Osmosis Press, as well as other books by Guillemot Press and many other presses producing important work in this field. Rose is of course renowned for her archaeological artwork, including her work on Seahenge for the recent British Museum Stonehenge exhibition. It was an enormous privilege to collaborate with her on this project. Her collage work for THE SLEEPING PLACE not only adds another rich layer to the book, image and text working together, but also creates new spaces for the reader's creative response to the landscape. And, as always, Rose's work brings an intelligent integrity, compassion and humanity to archaeological enquiry.

I've written above about the influence of the book Theatre/Archaeology by Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks on the development of my poetic for this book. I want to quote them again in this context. They advocate for a new way of making the archaeological record, including 'mutual experiments with modes of documentation which can integrate text and image'. They talk about the importance, when coming face to face with the mysteries of the past's material traces, of creating 'joint forms of presentation to address that which is, at root, ineffable' (Theatre/Archaeology, 2001, p 131). For me, addressing the ineffable is able to happen, if anywhere, across the spaces and relationships of THE SLEEPING PLACE's images, text and design.

But, at a much earlier stage, it was doodling rather than art which helped me shape THE SLEEPING PLACE. Rather than textual, my first exploratory response to engaging with the archaeological archive was with sketches of lively skeletons dancing across geographical maps and site plans. As these cartoon skeletons increasingly started to resemble letters and words, so the ideas for how I might structure my textual response started to emerge.

And now these little skeleton doodles have a new role in this project, appearing on my handsigned extracts from the text which will accompany the first purchased copies of the book. As I inscribe each page of the published text with these loose-jointed doodles, they emphasise the open-ended nature of this book and the discovery of more and more skeletons just waiting to be made.

vi. A little piece of grave robbery

Chalk sketch of 'sleeping' skeleton

Seven is a significant number for this book. It operates in a very different way to the numbered burials 1-223 which are used as a procedural 'hook' for my use of a textual constraint based on the archaeological site map. 7 is more mysterious. With its accompanying 1 2 3 4 5 & 6, 7 appears in various configurations throughout the book, straddling the gaps between the poem's sentences much as did my little skeleton doodles in an earlier draft. These more symbolic numbers arrived in the book as a result of a poetic ritual involving a minor grave robbery.

Although my primary approach to a linguistic staging of a Saxon burial ground involved using various textual constraints and grammars, I found that ethical and affective considerations to do with grief, death and the mysteries of mortality started to assert themselves. I became increasingly struck by the coincidence that the hillside beneath which the Saxon burial ground was excavated was also the site of Lewis Carroll’s grave. I began to revisit what this might mean for my text. Dodgson (‘Lewis Carroll’) was of course a mathematician and like Stein (who was herself a close friend of mathematician A.N. Whitehead) found correspondences between mathematics and language as a symbolic and relational system capable of generating meanings beyond the semantic (this is the basis for Carrollian nonsense). As I started to contemplate Dodgson’s interest in mathematics, I found some numerical symbolism and ritual entering the text. Although I am a little sceptical about ritual I am also drawn to its generative power, and so I followed where it led.

And where it led was to an act of grave desecration. In the book, I describe this incident as follows:

7 pieces of chalk ritual.

‘May 2021. I perform a ritual at the burial site itself. I find a grave has been opened in the Victorian cemetery in order to repair its monument. The human remains have been temporarily moved but when I look into the grave opening, I see sockets of chalk and knuckles of chalk-flint. Carbon unites bone and chalk in the ground. I steal 7 pieces of chalk from the open grave and form them into the shape of a human body. This creature I lay out on the earth. It resembles a skeleton curled on its side or a foetus. My ritual is galvanised by my grave robbery. The 7 stones now enter my text, virtual subjects hosting my decentred grammar but creating a new question of how to combine the symbolic 7 with the pragmatic 223. The procedures I used to create my initial draft loosen and slide, and something more mysterious starts to animate the text.’ (THE SLEEPING PLACE, ‘Timeline’ notes).

Detail from Rose Ferraby’s collage artwork, back cover.

This more mysterious and affective approach started to dominate the closing stages of the text’s many drafting cycles. To an extent, this remains mysterious to me, but I believe it to be, in some ways, a return of the mortal griefs and terrors initially banished from the text by its procedural response to human burial. I was keen that my skeleton doodles would give way to numbers in the text, not only because of the more open-ended work done by the latter, but also to clarify the visual poetic of the book and to allow Rose Ferraby's rich, suggestive and profound collage to do its work across the fullest range of concerns (some of them barely surfaced) by the written text.

vii. ‘a missing bead’: word-strings threaded through the text

Saxon glass bead (replica), Surrey burial ground, grave 223*

Archive photograph of some of the actual Saxon glass beads found during excavations.

During the 1920s excavations of Saxon burial site, a large number of glass beads were dug up alongside bones, pottery, pins and brooches. The strings themselves had rotted and so the beads had rolled apart. These beads were re-strung by museum staff in a creative approach to determining their original order. This resonated with my own project and so I adopted this as an additional textual strategy.

This additional textual strategy drew on an interactive performance in which members of the audience were invited to participate in selecting coloured beads and deciding on their order. I used modern Murano glass beads for this performance but as far as possible, I duplicated the colours of the Saxon beads: red, blue, green, silver, black etc. I also made space for the broken and missing beads noted in the archaeological site report. Each bead was linked to a bank of text fragments and so each time the audience reselected a string of beads, this led to a new iteration of the text.

Modern Murano glass beads used for bead-stringing performance.

Part of a Saxon glass bead string (replica)*

These word-strings are threaded through THE SLEEPING PLACE, forming a cohesive ribbon of repeated words, sounds and rhythm which link together the sections of text organised around burials. And these bead sections of the poem have a further, meta-textual function, figuring and drawing attention to the way words and phrases have been strung and restrung to make the body of the text. They foreground the way my compositional process has sometimes involved treating words as if they were beads– matching them by look and sound rather than semantics, much as the museum staff restrung the beads based on their colours and patterns. The patterning and rhythms of the way the beads are strung suggests a way of reading the text that takes the emphasis away from the semantic meaning of individual sentences, and directs it towards the changing relationships between words and phrases. As each new archaeological find changed the meaning of previous 'finds' for Lowther's team, so each 'restringing' of words creates new possible meanings for the reader to construct.

This brings me back to my ethical dilemma around using human grave numbers as part of a procedure of random text generation, and the push-pull between using these material traces creatively to construct a past in the present, and an abiding sense of what is irretrievably lost: those missing beads. In THE SLEEPING PLACE itself, these tensions remain unresolved and play out across the text, resolving temporarily but then rolling apart, waiting to be restrung.

THE SLEEPING PLACE is out now and available here.

This article first appeared as a series of blogposts on Susie Campbell’s website.

*all replica Saxon glass beads made by Tillerman Beads