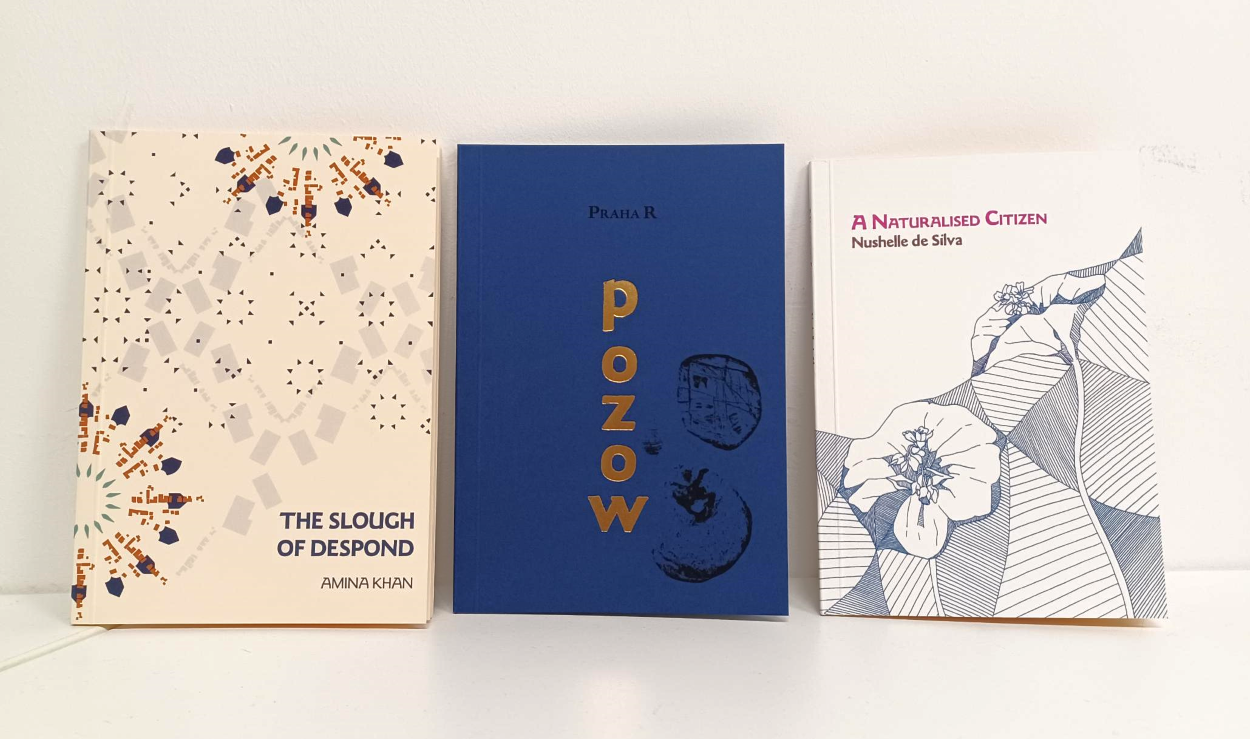

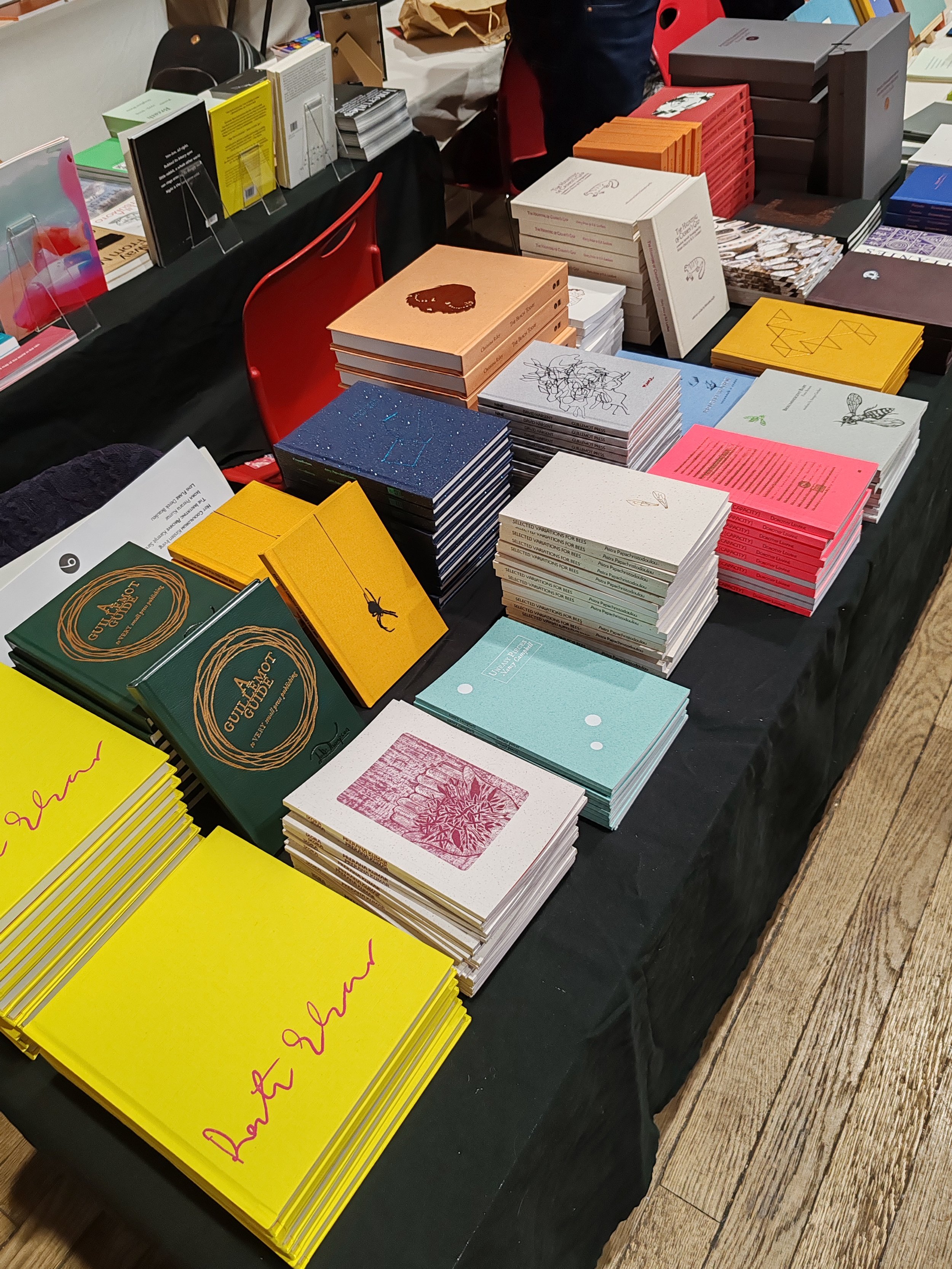

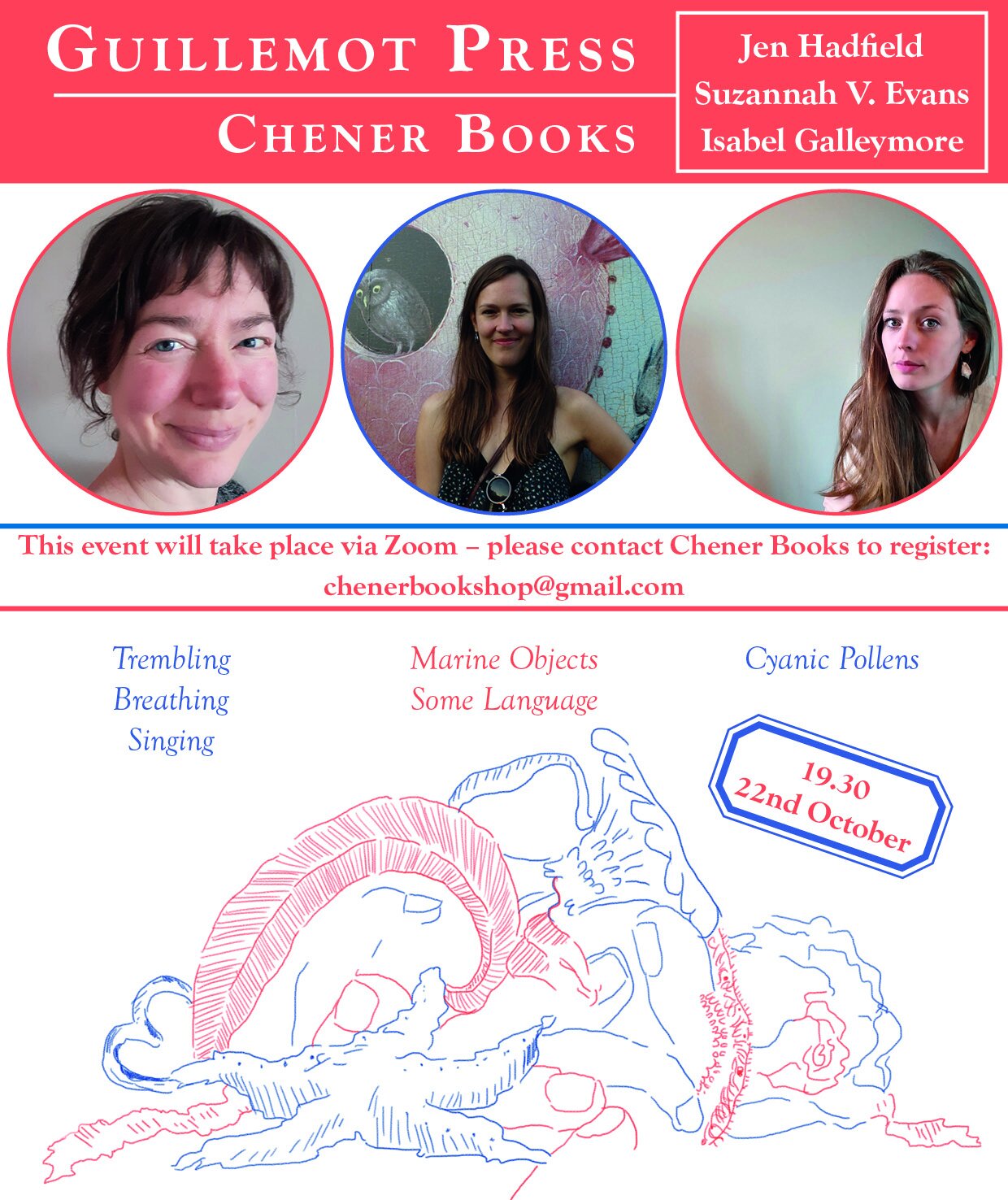

Jules Laforgue (1860-87) is best known as one of the pioneers of free verse and for his influence on anglophone poets including T. S. Eliot. But this inventive French poet was also one of the earliest theorists of Impressionism. In 1881, he became the secretary of the distinguished art collector Charles Ephrussi and had the occasion to see brand new works by artists including Pissarro, Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Manet, and Mary Cassatt. He began to publish art criticism in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, and later as the reader to the German Empress Augusta he explored galleries in Berlin, Dresden, and Munich. Laforgue carried his interest in Impressionism into the shifting perspectives and careful irregularity of his own poetry, which the novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans praised as ‘le véritable impressionnisme’ (‘true impressionism’). In 1883, he began writing his essay on Impressionism – an extract of which is translated by Tina Kover for All Keyboards are Legitimate: Versions of Jules Laforgue (Guillemot Press, 2023). The full essay is now available to read in Tina Kover’s translation below.

Impressionism

The physiological roots of Impressionism—the bias in favour of line-drawing. Recognising that, if the work of painting stems from the brain, from the soul, it does so solely by means of the eye, and that the eye is thus to painting as the ear is to music; then the Impressionist is a modernist painter who, gifted with extraordinary sensitivity of sight, disregarding the pictures amassed in museums through the centuries, leaving behind the approach he learned in school (line, perspective, colour) through living and seeing, honestly and simply, in the brightness of the open air—that is, outside the dim confines of his studio, whether it be in the city street, the countryside, or even some well-lit interior, has succeeded in restoring his own natural sight, and in seeing naturally, and painting simply, just as he sees. I will explain:

Aside from the two great illusions of art, the two criteria which aestheticians have long banged on about, Absolute Beauty and Absolute Human Taste, there are three crucial illusions by which technicians of painting have always lived: line, perspective, and studio lighting. It is to these three points, which have become second nature to every painter, that the three advances made by the Impressionist formula apply, namely: form, obtained not by line-drawing, but by vibration and colour-contrast alone; the replacement of theoretical perspective by a natural perception of colour vibration and contrast; and studio lighting—that is, the shift from working on a painting, whether it represents a city street, the countryside, or an artificially-lit drawing room, in the unchanging light of the painter's studio, and at all hours of the day or night—to working in the open air, painting in close proximity to the subject, however impractical this might be, and in the briefest possible time, given how quickly light conditions can change. Now let us examine these three points, these three dead-language procedures, turning them from a school-room exercise into an act originating on the playing-field of light and Life itself:

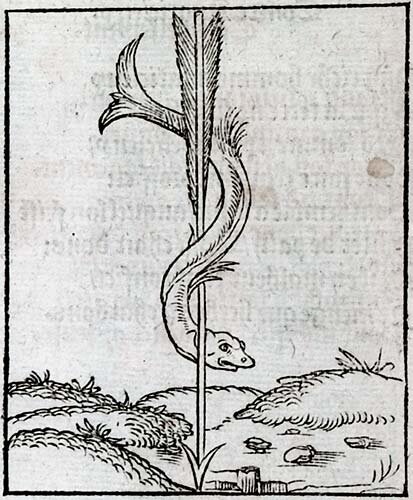

The bias in favour of line-drawing is an old and deep-rooted one, whose origin must be sought in the first human sensory experiences. The primitive eye, knowing only white light with its solid, impenetrable shadows, and thus unaided in its experience by the perception of nuanced shades, turned to tactile experiences. Thereafter, by continually making useful associations, and then by passing on to subsequent generations this improved understanding of the link between the abilities of the tactile organs and the visual ones, the sensing of form shifted from the fingers to the eye. The retention of form does not lie solely with the eye; the eye, in its ongoing refinement, developed the ability to see sharp lines for the ease of its own perception, and it is from this fact that the childish delusion that we can translate reality, in all its vibrancy and lack of flat planes, by line-drawing and linear perspective originated.

In essence, the eye can perceive only luminous vibrations, just as the acoustic nerve perceives only sonorous ones. It is for this reason that the eye, after having first adapted, refined, and systematized the tactile powers, has created, developed, and maintained itself in this state of delusion through centuries of line drawings; and so its evolution as an organ of luminous vibration has been severely delayed in comparison to that of the ear, for example, and its intelligence with regard to colour is still at a rudimentary level. Thus, while the ear in general, like an auditory prism, has no difficulty analysing harmonics, the eye sees nothing but light, and that synthetically and crudely, and has only a faint ability to break this light down into the spectacular sights provided by nature, despite its three fibrils, described by Young, which act like the facets of a prism. And so, a natural eye—or a refined eye, rather, because this organ must return to a primitive state, ridding itself of tactile illusions, in order to evolve artistically—disregards tactile illusions and their convenient, dead-language emphasis on line, acting only in a state of prismatic sensitivity. Eventually it becomes able to see reality in the living atmosphere of forms, broken down and refracted, reflected by beings and by objects, in infinite variations. This is the first hallmark of the Impressionist eye.

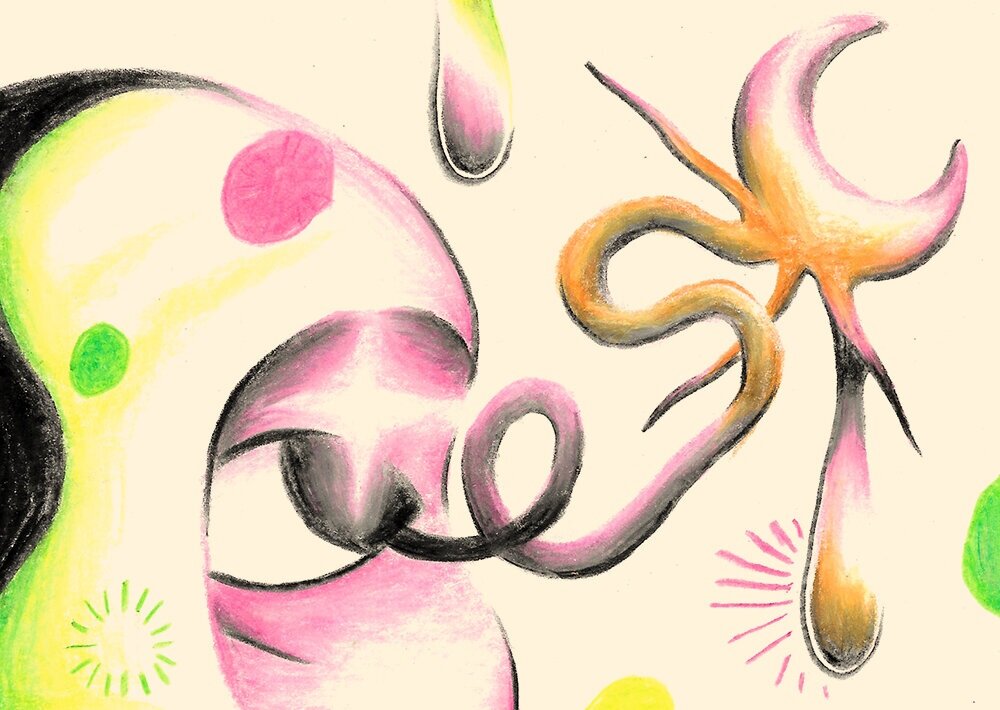

The Academic Eye and the Impressionist Eye—a polyphony of colour. In a landscape drenched with light, in which figures appear as if executed in coloured grisaille, and where the academic painter sees only an expanse of white light, the Impressionist sees this light as bathing the whole, not in a dead whiteness, but rather a thousand vibrant, clashing colours in rich, prismatic, fragmented shades. Where the Academic sees only the external outline of each object, the Impressionist sees the real living lines, without geometric form but composed of a thousand irregular brushstrokes, which, from a distance, create life. Where the Academic sees things positioned in their respective, regular patterns, like a skeleton reducible to a pure theoretical diagram, what the Impressionist sees is based on a thousand nuances of tone and effect, by shifts in appearance in keeping with the nature of things, which is not fixed, but ever-changing.

In short, the Impressionist eye is the most advanced in human evolution, one able to perceive, and to render in paint, the most complicated combinations of tint and hue known to man thus far.

The Impressionist sees and paints nature as it is; that is, solely in vibrations of colour. There is no line, no light, no relief or perspective or chiaroscuro; none of these childish classifications truly exist; everything comes down to vibrations of colour in the end, and can be captured on canvas through vibrations of colour alone.

In the small and exclusive exhibition currently on display at Gurlitt’s gallery, this formula can be seen in the work of Monet and Pissarro in particular, where everything is conveyed by means of a thousand delicate brushstrokes, dancing in every direction like coloured straws—all of them competing to produce the overall impression. No longer an isolated melody, the whole is a symphony, alive and changing, like Wagner’s 'forest voices' battling to become the great voice of the forest, like the universal Unconscious, the law of the world, that single, great, melodic voice arising from the symphony created by the consciousnesses of peoples and individuals. This is the guiding principle of the plein-air Impressionist school. And the master’s eye will be the one able to perceive, and to render in paint, the shadings, the subtlest fragmentations, on a simple flat canvas. This principle has been applied—not merely routinely, but ingeniously—by some French poets and novelists as well.

The erroneous education of our eyes. As everyone knows, we do not see the colours of the palette in themselves, but rather according to the illusions imparted to us by the paintings of centuries past and, above all, by the light that defines our perception of the colours themselves. (Compare, in photometric terms, Turner's most dazzling sun with the feeblest candle-flame.) An innate, reflexive, harmonious agreement, if you will, arises between the visual impression caused by a landscape and the feelings aroused by the paints on a palette. This is the proportional language of painting, which grows richer as a painter’s visual sensitivity improves. The same is true for scale and perspective. Dare I go further, and say that, in this sense, the painter's palette is to natural light, and to its plays of colour on reflecting and refracting realities, what perspective on a flat canvas is to the depth and the real planes of spatial reality? These two relationships are the tools of a painter’s trade.

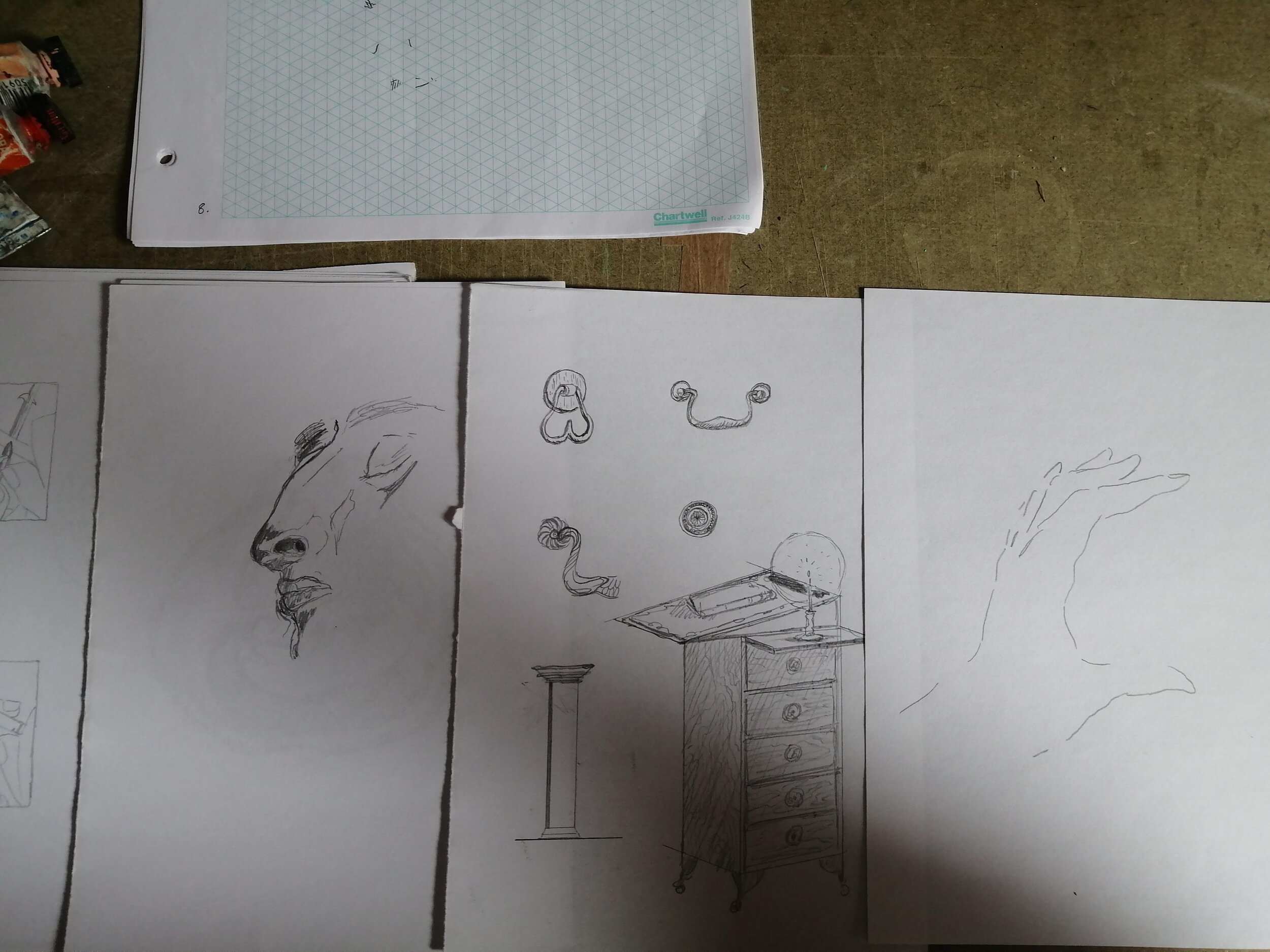

The changeability of landscape, and of the painter's impressions. To you, the critics who codify what is beautiful and steer the progression of art, I present a painter who sets up his easel before a landscape that is rather uniformly lit—in the afternoon, for example. Let us imagine that, instead of painting this landscape over several sittings, he has the good sense to set down its colours in fifteen minutes—in other words, our painter is an Impressionist. He arrives on the scene with his own individual perceptive sensitivity, which, depending on how tired he is, or how much care he has taken of himself, will be either blinkered or alert—and this sensitivity is not that of a sole organ; rather, it consists of the three competing sensitivities of Young’s three fibrils. Depending on the state of fatigue or preparation the painter has just been through, his sensibility is at the same time either bedazzled or receptive; and it is not the sensibility of a single organ, but rather the three concurrent sensibilities of the Young's fibrils. Over the course of those fifteen minutes, the illumination of the landscape - the vivid sky, the earth, the greenery, everything that makes up the intangible network of its rich atmosphere, with the endlessly rippling life of its invisible reflecting or refracting corpuscles, will have existed in infinite variation—will have, in a word, lived.

In the span of those fifteen minutes, the painter’s visual sensitivity will have changed, and changed again; its appreciation of the proportional constancy and the relativity of the landscape’s tones will have been disrupted. Imponderable mergings of hue, contradictory perceptions, minute distractions, subordinations, and dominations will have occurred, and with them variations in the reactive power of the three optic fibrils, among themselves and with regard to the outside world; infinite, and infinitesimal, conflicts.

Here is one example out of millions: I see a particular shade of violet. I look down at my palette in order to mix it there, and my eye is uncontrollably drawn to the whiteness of my own sleeve. Thus my eye has changed, and my violet suffers in consequence. And so on, and so on.

In sum, then, even if a painter spends a mere fifteen minutes before a landscape, his work can never truly reproduce the fugitive reality; rather, it can only record one person’s unique visual perception of a moment in time which will never occur again for that individual, in response to a certain landscape at a single, luminous instant, which, likewise, can never be duplicated.

There are roughly three states of mind, when one is viewing a landscape: the growing acuity of one’s optical sensitivity under the stimulus of this new sight; the peak of that acuity; and, finally, the gradual onset of nervous exhaustion. To these we add the infinitely changeable atmosphere of the best gallery where this canvas will be exhibited, the rigorous daily mingling and clashing of the colour-tones contained within it. And finally, the unique individual perceptions of its viewers, each one possessing an infinite number of singular moments of feeling.

The object and the subject are thus always in permanent motion, intangible and fleeting. Flashes of identification between the subject and the object are reserved for the genius alone; seeking to codify these flashes is nothing but a schoolroom farce.

The double Illusion of ultimate beauty and the ultimate man—Innumerable human keyboards. Those who embrace the old aesthetic have tended to prattle on about one or the other of two illusions: ultimate Beauty, which is taken to be objective; and the ultimate man, considered subjective—in other words, Taste.

Nowadays we have a better sense of the Life within us and outside us.

Each man is, according to the moment in time he occupies, his hereditary and social circumstances, and his stage of personal evolution, a kind of keyboard, on which the external world plays in a certain way. My own keyboard is perpetually changing, and it is unlike anyone else’s. All keyboards are legitimate.

Likewise, the outside world is an ever-changing symphony (as in Feschner’s law, which states that the perception of difference is inversely proportional to the intensity of this difference).

The visual arts spring from the eye, and the eye alone.

There are no two eyes in the world that are identical, either as organs or in their sensory powers.

All of our organs are in a state of vital competition: in a painter it is the eye that is dominant; in the musician the ear, in the metaphysician, a certain awareness, etc.

The eye most worthy of admiration is the one that is the most highly evolved, and consequently the most admirable painting will not be the one that embodies the academic fantasy of “Hellenic beauty”, “Venetian coloration”, “Cornelian thought”, etc., but rather the one that reveals proof of this evolved eye the refinement of its nuances, or the complexity of its lines.

The atmosphere most favourable to the freedom needed to evolve this way could be obtained by eliminating schools, juries, medals, and all such childish contrivances, the patronage of government, the parasitism of critics who lack taste, nihilist dilettantism, and the kind of anarchy open to any influence which reigns among French artists today: Laissez faire, laissez passer. The law follows its own developmental instinct, despite human interference, and the wind of the Psyche blows wherever it will.

Definition of plein-air. Plein-air, the method used first and foremost by the landscape artists of the Barbizon school (its name taken from the village near the forest of Fontainebleau), does not mean exactly “open air”. The plein-air of Impressionist landscape painters applies to their work as a whole, and means the painting of people or objects in their customary environment: the open country, candlelit drawing-rooms or simple interior spaces, streets, gas-lit corridors, factories, markets, hospitals, etc.

An explanation of apparent Impressionist exaggerations. The ordinary eye of the public and the non-artistic critic, who have been conditioned to see reality in the stable harmonies depicted by so many mediocre painters, is powerless compared to the keen eye of the artist who, more sensitive to variations in light, will naturally record on his canvas those rare, unexpected, and unfamiliar nuances of illumination and shade that may cause the blind to accuse him of deliberate eccentricity. And, truly, we must make allowances for an eye naturally, even wilfully disdainful of the seeming hastiness of these impressionistic works painted in the first heady rush of sensory intoxication at the sight of a rare and unexpected reality; artistic tastes with regard to the world as it is are generally conventional ones, sensitive to new spice, and is not all this furore more artistic, more alive, and thus promising of more richness for the future, than the old, dreary, unchanging academic recipes?

An agenda for future painters. Some of the most vibrant, daring group of painters that has ever been seen, and the most sincere, living subjected to derision or indifference as they do, and in near-poverty as well, with only the voices of a small segment of the press raised in support of them, are now demanding that the State cease its interference in the art world, that the School of Rome (the Villa Medici) be sold, that the Institute be closed down, that medals and other awards be abolished; they are demanding that artists be allowed to exist in the state of anarchy that is life, each one left to make his own way, protected from and unhindered by academic teachings living off the past. No more official definition of beauty; the public will learn on its own to see for itself, and will gravitate naturally toward those painters whose work interests them, modern, alive, and not the dead art of Greece or the Renaissance. No more official exhibitions and medals than there are for writers. Just as these writers labour in solitude and seek to place their work with publishing houses, so artists will work as they choose, and seek to place their paintings in the windows of art galleries; these will become their exhibitions.

The frame in relation to the painting. Exhibitions put on by independent artists have substituted an intelligent, refined, fashionable selection of frames for the perennial moulded gilt ones which have become such an integral part of academic cliché. A sunlit green landscape, a blonde page in winter, a room glittering with twinkling candles and bright-hued garments—all require different styles of frame, which their painters alone can devise, just as a woman knows best which fabrics and powders suit her best, and which boudoir wall-hangings will set off her complexion, her expressions, her mannerisms to best advantage. I have seen smooth-surfaced frames in white and pale rose and green and jonquil-yellow; others are extravagantly multicoloured, combining any number of styles. An interior with dazzling lights and colourful clothes require different sorts of frames which the respective painters alone can provide, just as a woman knows best what material she should wear, what shade of powder is most suited to her complexion, and what colour of wallpaper she should choose for her boudoir. Some of the new frames are in solid colours: natural wood, white, pink, green, jonquil yellow; and others are lavish combinations of colours and styles. There has been some resistance to these frames in the official exhibitions, but in the end this backlash has produced nothing but gaudy bourgeois imitations.

Impressionism is translated by Tina Kover. Tina is the award-winning translator of over thirty books from French, including Négar Djavadi’s Disoriental, Alexandra Lapierre’s Belle Greene, and Anne Berest’s The Postcard. She leads literary translation workshops for the American Literary Translators Association and masterclasses in literary translation for Durham University. She is also the co-founder of Translators Aloud, a YouTube channel that features literary translators reading from their own work.